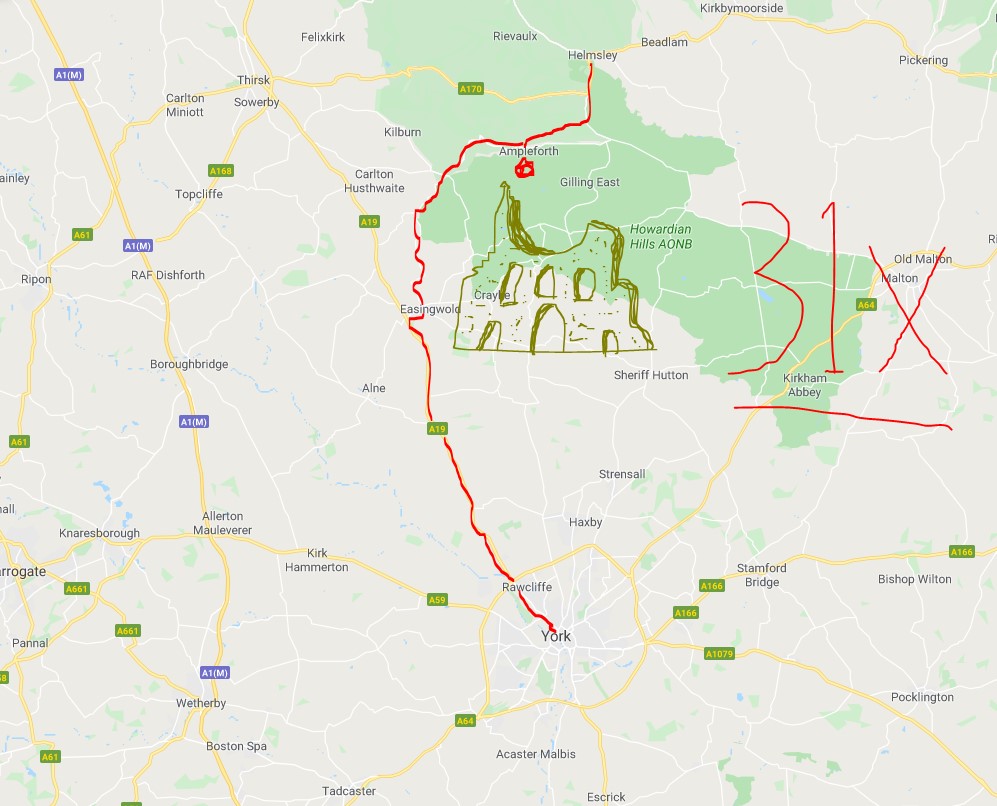

Route: 31X, Helmsley to York

Operator: Reliance Motor Services

Timetable: 3 per day (Mon-Fri); 4 per day (Sat, last run is part-route to Easingwold); no Sunday service

Time: ~1h 10m

Cost: £5.60 Single

Date of Trip: 16/10/19

Face & Heel: Ian & Luke

‘Luke!’ I say, pointing towards a window heaving with local produce. ‘Look, it’s Hunters of Helmsley.’

‘Oh yeah, it says it’s the best small shop in the country,’ he replies, the tip of his tongue circumnavigating his lips in anticipation. ‘I think I’ll get my dinner there.’

‘No, Hunter…Helmsley…Triple H.’

‘What? What are you on about?’

‘The wrestler. Triple H, that’s his name. Hunter Hearst Helmsley.’

‘I don’t care, I hate wrestling.’

As the fourteen-time WWE champion began his grappling career almost two decades before Hunters opened for business in 2008, its owners must have named the award-winning deli in his honour. It’s an accolade I’m sure he’ll be proud of. Perhaps as much as when Motörhead played his theme tune live before his match with The Undertaker at Wrestlemania X-Seven in 2001.

Helmsley is a beautiful little town on the fringe of the North York Moors, centred around a broad market square which doubles up as a car park. Looming over it is an ostentatious monument and statue for William Duncombe, 2nd Baron Feversham. An Ultra-Tory MP – think the extreme right wing of today’s Conservatives – who, when he wasn’t busy suppressing Catholics, enjoyed discussing the minutiae of bullocks.

Perhaps misunderstanding the family lineage, his great-great-grandson, Jasper Feversham, made a career from filming bollocks. An adult movie impresario, his father disinherited him from a £46m fortune in disgust. When his old man’s peerage passed onto him, the press inevitably dubbed him the Porn Baron.

“He’s Broken in Half!”

We make for Duncombe Park, which still houses the ancestral pile, for Luke to scoff his hulking artisan cheese butty and an unsuccessful attempt to duck out of the rain. The Fevershams have a ruined 900-year-old castle in their back garden, not to mention the National Centre for Birds of Prey. In the end, we see neither as our allotted forty-five minutes are ebbing away, but despite its slight size, Helmsley is worth a day of anyone’s time.

Grapple fans are well-served on the 31X, too. With his stocky build and colossal beard, the driver would make a tremendous heel. I, of course, mention this to Luke.

‘Would you stop going on about the wrestling,’ he says. ‘It’s stupid. I don’t even know what a heel is.’

‘It’s a baddie. Like Giant Haystacks.’

‘I don’t care, Burkey. Get a life.’

I know it’s stupid, of course I do, but that doesn’t prevent me from enjoying it. In fact, that’s what makes it fun. The more ridiculous, the better; a demented speech from Paul Heyman, Mick Foley’s crash test dummy impersonations, Edge hamming it up. Nobody gets their kicks from watching Greco-Roman wrestling. It’s the dullest sport at the Olympics. Other than archery, of course.

We head south, where a grand sandstone archway stands in the middle of nowhere, a couple of miles out of town. Built in tribute to Nelson in 1806, the year after his death off the southern coast of Spain during the Battle of Trafalgar, it marks a lesser-used entrance onto the Dunscombe estate.

The showers fizzle out at last. This treats us to an unimpeded view of green hills bubbling from the surface as we fluctuate in altitude along what is already proving to be a lovable route. We turn into a heavily wooded side road, where thousands of pine trees stand, stripped of their lower branches, presumably for use as Christmas trees.

‘It’s very Center Parcs-y,’ is Luke’s spot-on assessment. Even better, there’s no archery.

Who Says Phalanx, Eh?

A signpost forbids caravans from using nearby Sutton Bank. A solid idea considering it has a one-in-four gradient, a hairpin bend, and around 500 larger vehicles each year either get stuck or shed their loads on it. Instead, we glide down a 12% slope of our own into Ampleforth, a village split between the generous Victorian terraces on the main drag, and the 1960s council estate further downhill.

It’s heading towards the latter where the driver threads the eye of a needle, squeezing a path between a phalanx of parked cars outside the local school. He does a lap of the estate, doubles-back the way we came, and stops to take photos of the offending vehicles making his job more difficult, saving them in a file named ‘evidence’.

Autumn arrives unannounced as we ricochet along the bumpy road to Wass. A monsoon of golden leaves flutter onto the bus’s windscreen before they’re collected and flung aside by its hard-working wipers. The roadside hedges are just high enough to prevent us from seeing anything other than a green wall on either flank, until they drop away for a dramatic reveal of the crumbling remnants of Byland Abbey.

Its remaining window arches and pillars have defied the ravages of the weather in this exposed spot since Henry VIII saw his arse and set the Dissolution into motion almost five hundred years ago. A bout of cultural vandalism unequalled to this day, he enacted it on various shady pretexts, including stymying the wealth of religious orders to finance banquets and the occasional war.

There was also the minor matter of cocking a snook at the Vatican, who via the various monasteries owned around a quarter of England’s arable land. It wasn’t keen on the King forming his own breakaway church after putting the kaibosh on his divorce from Catherine of Aragon in 1533.

Abbot John Ledes surrendered the Abbey and anything of value to Coppernose five years later. The locals joined in on the act over the centuries, requisitioning much of its stone for their homes and the cosy pub just across the road. Even so, what remains is still an incredible sight.

On Not Appreciating Chalk Art

We catch glimpses of another landmark as we hurtle along the back roads of Hambleton: the Kilburn White Horse. A mere foal compared to the more stylish hillside nag at Uffington–160 years-old compared to 3,000–but what it lacks in age it makes up for in size. Covering 1.6 acres, it’s the largest chalk figure in the UK.

‘It’s not very good, is it?’ I ask, breaking out my special box of probing questions.

‘It depends,’ Luke replies. ‘It looks more like an elephant from here.’

‘The Kilburn White Elephant?’

‘Well, I can’t tell it’s a horse.’

A lady with red earbuds is our first pick up as we reach the Cotswoldian-style village of Coxwold, with its broad main street given over to vast grass banks and idyllic cottages, while its old-fashioned streetlights appear to be bulb-less and for decoration.

Lush fields extend to the horizon toward Thirsk, so frequently signposted today, but destined to go unvisited on this adventure, while a handful of fields of sweetcorn beyond Husthwaite have passed their peak and stand forlorn, heavy and unpicked.

Easing into Easingwold

We navigate the twisting lanes into Easingwold, which has handsome Georgian homes lining the course into its compact centre. It’s the type of robust housing stock the smartest of the Three Little Pigs will have used to thwart the Big Bad Wolf.

Easingwold is the type of quiet, out-of-the-way place where nothing grave has ever happened and you can’t imagine ever will. Even from our seats, it exudes nothing but contentment with its lot. Even the three new shoppers who board beside the canopied market square all radiate a genial aura. It’ll win no prizes from Britain’s Most Exciting Towns committee, but it’d be another wonderful self-contained pocket of North Yorkshire to spend a night or two.

The A19 presents the first real chance for drivers to open their throttles since leaving Scarborough, scything through the flat expanse of the Vale of York. We whistle along at such a clip that two of the bus’s windows swing open. The sudden gale scatters the pages of the novel the lady in front of us is reading and thrusts her hair skywards, sculpting it into the shape of a cassowary’s aerodynamic casque. Leaping into action with uncharacteristic swiftness, Luke slams one window shut, I grab the other, but both continue to rattle and threaten to burst asunder with each dab of the throttle.

Our progress slows outside Shipton by Beningborough, where a police van with its blue lights flashing straddles most of the carriageway, allowing a recovery van to clean up after an accident bad enough for us to wince at the mangled wreckage of a car. This entire stretch of road is almost free from human life, with just the very occasional linear commuter community hugging the busy artery into York. In contrast to the city itself, its hinterland is dreary in every direction, with 2D landscapes not hinting at the two thousand years of history ahead.

York is easily my favourite city in the north. Although its famed city walls are mostly a 12th century Norman reconstruction of the earlier Roman fortifications, its outskirts are still pretty enough to give it the feel of the world’s largest village. Ducks, ponds, and greens are around every other suburban bend.

‘It reminds me of Cambridge,’ Luke says. ‘Except there you get a pub in the middle of a row of houses.’

‘Do you mean like that?’ I reply, as The Jubilee appears with impeccable timing.

‘Yeah, but not as boarded up as that one.’

A minute later, after we breeze past the National Railway Museum (which I got lost in once when I was a little boy and cried until a member of staff found me), we are off the 31X, and deposited right by those sturdy city walls.

‘How’s your day been, then?’ I ask Luke, who has finally broken his bus adventure duck.

‘It’s been good,’ he says, rubbing his left eye. ‘But I’ve got a sore arse now.’

‘That’s a sign that you’ve had a good day.’

‘If you say so.’

0 Comments