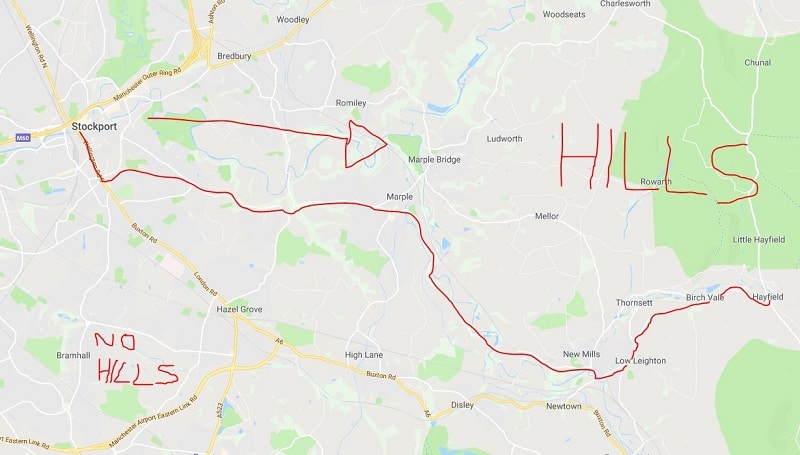

Route: 358, Stockport to Hayfield

Operator: Stagecoach Greater Manchester

Timetable: Hourly at xx30 or xx45, Mon-Sun

Time: 50 minutes

Cost: Part of a £5.80 SystemOne Day Ticket

Date Of Trip: 1/3/19

“I’m learning all the four-letter words now. There’s about 6,000 of them in all.”

This is my friend Orla. She’s not talking about mastering obscure obscenities, although they’ll definitely come in handy, because she is a certified black belt in Scrabble. After ticking off the two, three, five and most of the six-letter words, she is honing her wordsmith skills to an even finer point. If Scrabble was a platform game, she’d be a fearsome end of level boss, whirling Z, Q, X and J tiles towards you at a deadly velocity from the far side of the screen.

“Here’s one I did before,” she says, spinning her phone’s screen in my direction. “Along the top.”

“Finalized.” I whisper, squinting through the glare. “On two triple word thingies. Blimey, how many points did you get for that?”

“Oh, not that many. The other person put ‘Final’ and I hooked the ‘-ized’ on to the end of it, but still…”

Not only is Orla by far the best Scrabble player I’ve ever met, but she’s qualified for the 2019 national championships after a Top 8 finish at a recent tournament in Warrington. She’s got a world ranking and everything, and I don’t know anyone else with one of those in any other kind of pursuit.

I went through a spell of playing the Hasbro classic about ten years ago, even buying a comprehensive Scrabble dictionary, which I studied in forensic detail for at least an hour on the day it arrived, before it took up permanent residence in a box at the back of a cupboard.

Orla has always been an anagramaniac, lobbing out seven letter terms at will and claiming the 50-point bonuses that come with them. My brain just can’t see them at all, so I stick to sneaky spoiling tactics. In the equivalent of a football team holding the ball by the corner flag from the very first minute in order to eke out a goalless draw, I usually chip away with 2-4 letter words, appending them to other tiles so that the board looks like a compact garden trellis with minimal room for manoeuvre.

It’s a method frowned upon by serious players, but I can’t beat them on an open board, so I have to drag them down to my level, ie, the dirty Scrabble gutter.

Sensibly enough, bus operators tend to put smaller buses on their lesser-used routes, and although fewer than 3,000 people live in Hayfield, the suburbs of Stockport which lead to it are as packed as anywhere else in Greater Manchester. Even so, it’s still a welcome surprise that when the 358 appears, it’s a double decker.

Naturally, we hotfoot it onto the top deck where battle commences about where to sit. To put it bluntly, me and Orla are fussy buggers. Orla always gravitates towards the seat immediately behind the stairs, and in the interests of conviviality, I reluctantly follow her there. It’s within actual spitting distance from my natural harbour of the 3rd seat from the front on the left side of the aisle, but it feels like an alien world.

Fortunately for me, there’s a problem.

“Oh,

there’s no leg room at all.” Orla says, her crest entirely fallen. “I suppose we

can sit over there instead if you want.”

“Get in!”

Superior view of the road ahead secured, the bus chugs out of station and stops at the lights outside the Stockport Plaza. A theatre, cinema, tea room and cavernous Art Deco masterpiece, it’s a building which has lived several lives since it opened with a showing of 42nd Street in 1932.

Modelled on the Regal Cinema in nearby Altrincham, which was dubbed the ‘Cathedral of the Movies’ until it burnt down in the 50s, the Plaza straddled the last knockings of the silent era, and the births of 3D and CinemaScope. Unlike most picture houses of the day, it was fully equipped to screen the lot.

A decline in footfall which beset the industry in the 1960s saw it taken over by Mecca in the summer of 1965. It re-opened as a bingo hall and nightclub 18 month later, but at least it was being used and enjoyed. Plus, bingo is ace.

Mecca was ready to wash its hands of the Plaza by 1999, and with a very real threat of dereliction or even demolition, Stopfordians were rallied, the building was snapped up by The Stockport Plaza Trust and a grand restoration project was initiated.

It’s doors once again welcomed theatre and movie-goers from October 2000 and has been steadily coaxed back to its prime ever since. There can’t be many buildings garnished with more love from its local community than this one.

The lights eventually change, and the 358 makes its merry way up towards the A6. It’s only a brief foray onto what is Wellington Road South at this point, but we pass a cafe called The Scotch Egg, which has the most magnificent sign in the entire SK postcode. The ‘o’ in ‘Scotch’ is a cartoon of a scotch egg dressed in a kilt and tam o’shanter, while the wayward nature of its eggy limbs suggests it is mid-Highland Fling.

We dive left onto Hempshaw Lane towards Offerton. It’s one of Stockport’s more amiable districts, summed up by the A-board outside The Finger Post, which loudly proclaims it to be ‘PUB OF THE YEAR!’. That’s until you look a little closer, ideally under a microscope, and notice that just underneath it also says, ‘runner up’.

A giant ‘B’ comes into view just around the corner, painted onto the leviathan turret of what was once Battersby’s hat factory. They were the UK’s biggest producers of headwear in the first half of the 20th century, with its workforce of 1,000 signing off on 12,000 bowlers, boaters and trilbies per week.

The post-war years saw the populace letting their hair run free, literally as well as metaphorically, and the daily wearing of a titfer was no longer de rigeur. Before that, the outdoor wearing of hats, whether it was a fancy fedora or a working class cloth cap, wasn’t just seen as normal, but it was seen as completely abnormal if you didn’t have one.

The picture above was taken outside Wembley ahead of the 1923 FA Cup Final between Bolton and West Ham. Of the hundreds of men queuing up to gain entry into what became known as the White Horse Final, there’s only one person not wearing a hat, and he probably left his on the train.

It’s true that this was a special occasion, but there are a couple of theories as to why hat use fell into decline. One valid shout is the accessibility of the car, with the Ford Model T being a likely catalyst. As the progenitor of the production line vehicle, it shifted 15 million units during its 19 years of manufacture, and while the technology it used was hardly cutting edge, it did have one crucial component in place: a roof.

This roof wasn’t especially high, however, and most drivers would have to take their hats off while at the wheel. A habit was formed, and by the end of the 1920s, there were ominous warning signs for milliners.

The real slump started after demobilisation from the Second World War, where in a survey by the Hat Research Foundation, 19% of those who preferred to go bare headed said that they chose that look because they’d been forced to wear a hat in the forces. It may have been a mild sign of youthful rebellion, but more probable that it was an attempt to totally disassociate from what must have been a hellish experience.

That said, life for non-hat wearers was difficult in some towns.

Stockport and, just down the road, Denton, were the epicentres of the hat making world, and those who went hatless were often abused and intimidated for not supporting a local industry when the order book wasn’t anywhere near as fat as it used to be.

To make matters worse, rock ‘n’ roll appeared alongside Elvis’s quiff – never the most hat-friendly of hairdos. With the direction of travel obvious, Battersby’s and four more of the area’s major hat manufacturers banded together to form Associated British Hat Manufacturers in 1966, and despite gamely swimming against the tide, its final remnants were snuffed out in 1997.

Aside from a fella with shoulder-length hair a few seats behind us, there are no other passengers on the bus. That’s until an old lady with the coolest hand signal I’ve ever seen shuffles on. She’s wearing a beige coat and regulation grey perm, but as the 358 approaches she rolls her head and shoulders like a boxer being given pre-fight instructions, and lifts the index finger of her left hand into the air before lowering it to point directly at the driver. I don’t see her wink and say “Heyyyyyyyy”, but she was definitely thinking about it.

We dip into the Goyt Valley and when we emerge on the other side, we’re in Marple.

Named after Agatha Christie’s fictional amateur sleuth, I always had the impression that Marple was a bit lah-di-dah when I was growing up. It’s certainly got its pricier pockets, but its high street has a solid mixture of every day practicality and shops you just wouldn’t bother going in unless you had a few bob stored up in case you break something. It works, though, and with barely any empty units, it’s one of Stockport’s more thriving outposts.

It also punches well above its weight in the musical stakes, with a particular appetite for nurturing indie-rock hopefuls. Dutch Uncles, Egyptian Hip-Hop and the recently reformed Maple State have all stomped these not-so-mean streets. As strong as their output has been down the years, they’ve never reached the top of the hit parade, which another local lad, Timmy Mallett did in 1990 with his peerless rendition of ‘Itsy Bitsy Teeny Weeny Yellow Polka Dot Bikini’.

The song was produced by Andrew Lloyd Webber, and some would argue that it’s still his finest hour. Or finest couple of minutes, anyway.

Ostentatious houses greet us at the top of Marple Locks, with one cubist fusion of glass and wood apparently having been bolted onto the top of a bungalow. Every home on the row is completely unique, with one bravely using every building material known to mankind, another has ill-considered columns blocking the front door, and one revels in having a garage that looks like the Cookie Monster rendered in stone.

Mist descends as we make our way along Strines Road, and while we can’t see much beyond the silvery-grey veil of cloud, we do spot a cheeky goat bleating from on top of a shed. A pied wagtail joins in the fun and buzzes the bus for a few seconds before dropping down next to a newly bloomed cherry blossom.

The bus enters Derbyshire and is soon in the centre of New Mills, (love)heart of the Swizzles empire and the home of the Plain English Campaign. As the name suggests, they advocate the use of simple language to convey a message, so this blog is going to be in all kinds of trouble.

Their website even has a handy Gobbledygook Generator. It inhabits the mind of every blue sky thinking manager, every imagineer and every business conceptualist that has ever existed. Press the button and be teleported to a dreadful meeting anywhere in the world with phrases such as:

- It’s time that we became uber-efficient with our synchronised logistical resources.

- We need to get on-message about our ‘Outside the box’ modular hardware.

- The solution can only be deconstructed strategic flexibility.

It’s a hefty climb out of New Mills up Church Road, which morphs into Hayfield Road and puts us firmly back out into the sticks.

“That looks lovely,” I sigh to Orla as we gaze at the sleek slopes of Lantern Pike away to the left, “but I’m pretty sure I’d die if I climbed it.”

“Yeah, you probably would. And it’d be so boring.”

“I know. I mean, I like looking at hills from a safe distance, but it doesn’t mean I want to go up one.”

“The thing is,” she says, leaning forward, “there’s nothing there when you get to the top. It’s just a good view.”

Now, I’m not completely averse to walking. I’d even go as far to say that I enjoy it, it’s just that you won’t catch me traipsing, out of breath and dripping in my own juices, up the side of a mountain. I’m blessed with feet the size of Parma hams, but it makes finding appropriate footwear tricky. I bought some size 11 walking boots a few years back, but they were simultaneously too big and too small. Plenty of wiggle room for the toes, but I near enough had to take the laces out to put them on in the first place.

Soon after that, I had to get some new shoes for a job interview, and explaining my predicament to the attendant in Clarks, he courageously offered to measure my feet. I’d not had this done in the best part of 30 years, and anyone with the chops to go near my festering digits without wearing a hazmat suit should be awarded an MBE on the spot.

“Och, you’ll nae believe this, ma wee laddie” he gasped in what I assume must have been a Welsh accent.

“What, am I a size 8 or summat?”

“Not quite tha noo, yeer mair between a size 9 and 9 and a hairf.”

“Wow, really!?”

“Aye, but yee’ve goat tha muckle widest feeties ah’ve ever seen in ma boab.”

The man didn’t say exactly how wide, but it’d certainly explain why every pair of shoes I’ve ever owned ends up looking like the Incredible Hulk had ripped them to shreds after a couple of months. He brought over some special wide-fitting shoes, size 10, which I got on without the aid of a shoehorn, and what’s more, they fitted me like a glove. Or perhaps more accurately, a sock. Or a shoe.

You wouldn’t know it from the bus station, plonked right next to the bypass, but Hayfield is a classic Peak District village. With its stone cottages, picturesque bridges and cricket pitch right in the middle, you’d never expect it to have been the site of one of the UK’s most successful act of civil disobedience.

The mass trespass of 1932 saw hundreds of ramblers set off from Bowden Bridge quarry, heading for the untamed plateau of Kinder Scout which dominates this portion of the county. At 2,087 feet, it’s only the 194th highest summit in England, but as there’s nothing anywhere near as tall to the west, you can see as far as Snowdon and Plynlimon, around 100 miles away. That’s assuming none of them are covered in cloud, which as I’m sure you know, isn’t very likely.

The trespass saw game keepers, who fearing the dangers that Gore-Tex and walking poles would pose to their grouse, get into scraps with walkers. Half a dozen of the trespassers were arrested for their tussles (trespass has always been a civil, rather than criminal matter) and sentenced to between two and six months in jail.

This caused a torrent of public sympathy to flood their way, with 10,000 people attending a subsequent access rally at Winnats Pass, just on the other side of Kinder, in Castleton. Eventually, this led to the National Parks Act in 1949, with most uncultivated land being designated as ‘open country’ and, in order to keep ramblers in check, the advent of the Countryside Code.

There’s still no way you’d get me up there, though.

0 Comments