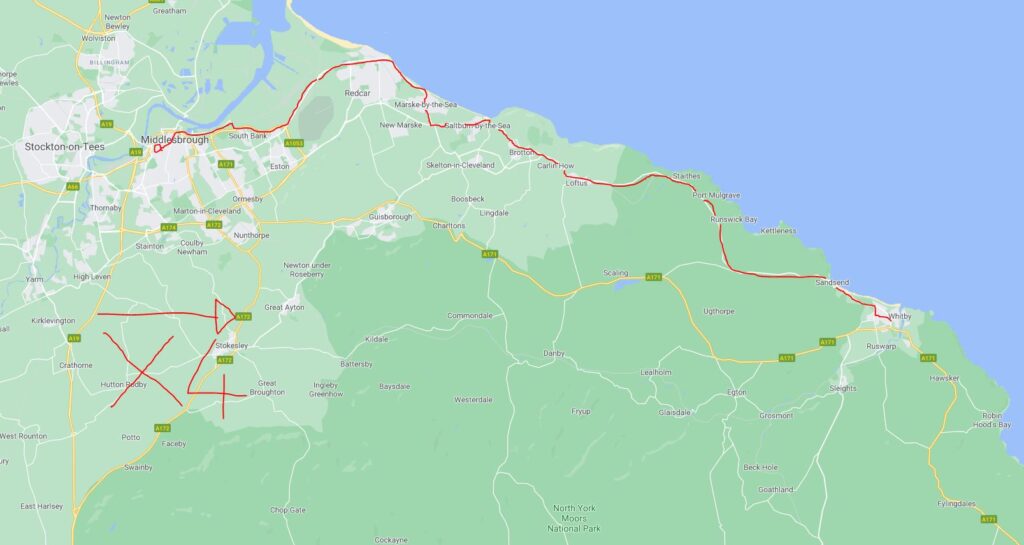

Route: X4, Middlesbrough to Whitby

Operator: Arriva

Frequency: Every 30 mins (Mon-Sat); Hourly (Sun)

Time: ~1h 50m

Cost: £13.50 Family Ticket

Date of Trip: 2/5/19

Marske of Zorro: Ian & Eleanor

‘Are you sure you don’t want to stick around for a while?’ Eleanor asks after a gallop through Middlesbrough’s retail heart.

‘Not really,’ I shrug. ‘Everyone I knew has moved on, and all the places I knocked about have been knocked down. You can’t put your arms around a memory, El.’

‘That’s a bit profound for you,’ she says.

‘That’s because it was Johnny Thunders. Oh yeah, look, there’s that McDonald’s where I nearly got beaten up.’

Middlesbrough is almost unrecognisable from when I lived here in the late 90s. There’s a whole new shopping district, where a nerdy-looking lad is making the most of his school being closed for local election polling, and earns a few bob by busking. He croons ‘You Lift Me Up’ on our first pass, ‘Flying Without Wings’ on our second, and I expect he bookends them with more Westlife and Boyzone bangers while we swan about.

It’s the tail end of a Thursday dinnertime, but the centre is heaving. Busier than most places at weekend, in fact. One notable aspect hasn’t changed, though: the taxis are still black with bright yellow bonnets. Rumour has it their introduction came about because they were so ugly that nobody would ever think to steal one.

Boro’s horseshoe shaped bus station was where I’d get the slow coach back to Manchester every fortnight to see Eleanor. I’d lug a bin liner full of dirty clothes into the luggage compartment of the National Express for the four-and-a-half-hour slog. It wasn’t that I didn’t know how to use a washing machine when I was eighteen – although in mitigation, I didn’t – it was more that I was chronically shy. Asking one of my peers in the halls of residence to show me what to do would have embarrassed me so much that you could’ve sizzled a steak on my cheeks. I even missed an entire module at uni because I couldn’t muster the courage to ask someone for directions to the room it was being taught.

We board the single decker X4, bagging the only spare double seat left, over the rear wheel. The bus swings out of the station, past the site of what was once the Tap & Barrel, a pub I took Eleanor into one Saturday night for a last pint behind heading back to my halls. There was shrieking above the jukebox from the function room upstairs.

‘Is there a gig on?’ I asked the barman.

‘Errrr, sort of,’ he replied.

‘Oh right. Is it a private party, or can anyone join in?’

‘Yeah, just head up if you like.’

Pints of cider in hand, we did just that. The guy taking the money at the top of the stairs seemed surprised to see us.

‘How much is it in?’ I asked, as the screams grew louder.

‘Are you sure you want to go in?’ he said, motioning to the half-open door away to his right. Through it was a woman dressed in more leather than a Longhorn herd, who was holding a hammer in one hand and a fistful of six-inch nails in the other. I looked to El for help.

‘It’s alright,’ she whispered, ‘I think we’ll leave it.’

We found a corner back downstairs and supped our drinks in bemused silence. It’s an Indian restaurant now.

The humidity onboard has reached saturation point, so it’s a blessed relief when passengers open all the windows in quick succession, letting in a ferocious breeze which swirls everyone’s hair into the shape of a Walnut Whip.

We pass Middlesbrough FC’s Riverside Stadium, by far the most unattractively situated major sporting ground in the country, almost encircled by undeveloped scrubland. There’s also the huge shell of an abandoned Sainsburys next door, which should’ve superseded the one across the street from the bus station, but they pulled out of the project in 2015 citing a change in trading conditions, i.e., they were taking a clobbering from Aldi and Lidl. Its husk has remained untouched ever since. Even the vast acreage of car park is closed off from learner drivers wanting to practise their three-point turns.

The A66 takes us by an industrial landscape ruled by companies whose names don’t rely on acronyms or abstract concepts. They keep things simple and just tell people what they do. Steel Benders UK. Tarmac Northern. Truckfix. If their collective MDs could rename Great Britain, they’d call it North Sea Island (Ltd.).

The series of roundabouts which spur off into various trading estates all have sculptures at their centre, the most striking being ‘Ladle of Steel’, which sees a huge red bucket suspended in mid-air as it pours a molten concoction onto its unsuspecting traffic island. The further we head out, the more indecipherable it all becomes. Unbroken miles of factories are all busy doing processes beyond my comprehension, with pipes as wide as a 747’s fuselage pumping into imposing cylindrical containers. The area’s influence on Blade Runner is obvious.

The largest of these colossi are the combined forces of the two Redcar steelwork plants. They dominate for miles on the way to the coast with their rusting infrastructure weathering before our eyes. If you didn’t know any better, you’d swear we were in the Chernobyl exclusion zone. Weeds grow unabated between black and yellow warning barriers, with much of the site abandoned after the extinguishing of it furnace (the second biggest in Europe) in 2015.

Between the two factories, although not visible from our vantage point, is British Steel Redcar: the least used railway station in the UK. Its four daily trains attracted a grand total of forty visitors in 2017/2018, but anybody who gets off has to stick around. The surrounding land is all privately owned, so wandering from the station would class you as a trespasser. If you leave the train here on the 0825 to Saltburn, you’ll be in for a nine-and-a-half hour wait until the next one back to Middlesbrough turns up.

A patch of bulrushes gives away a body of water hiding just behind a wall, and sure enough, we are right alongside Coatham Marshes. A haven for birds and twitchers alike, it somehow thrives between the crusty outflow pipes and corroded chimneys of these forsaken manufacturing skeletons. Coatham itself, now conjoined with Redcar, is not only the first place we pick up any new passengers, but it’s the first scheduled stop at all, almost twenty minutes in.

The ‘X’ in ‘X4’ denotes that this is an express service, or at least it does for its initial stage. Of the trio of newcomers, one is an old lady with a knitted poppy on her hat, while another is a profusely sweating bald man with a poppy red skull. In a daring move, he wears a bumbag around his neck like a choker.

All three jump off after just two stops, by which time we’ve reached Redcar town centre. It’s where a lad in his late teens joins, sitting on the opposite side of the aisle to us, and starts spraying himself with choking bursts of deodorant. He repeats this every sixty seconds or so as we zip along the seafront, the tide as far in as it’s possible to be, as we gaze at the wind farm propellers whirling away offshore.

‘What’s he doing?’ I mouth to Eleanor.

‘He must be paranoid that he stinks, I suppose,’ she whispers back.

‘But he doesn’t.’

‘Can you not smell the weed?’

‘No.’

‘Well, it’s him.’

The cliffs towards Saltburn lurch out from the depths a few miles distant. Their strata layers are as clear as day, turning from black to brown to a murky yellow as they gain altitude, like the world’s largest, but also most disappointing cake. Saltburn itself is anything but an anti-climax, though. With the aerosol fumes getting to evacuation levels, we hop off to find a cheerful resort. A windy waltz of its lofty perch reveals something I have a soft spot for: a cliff tramway.

Painted burgundy and cream, an immaculate wooden hut at the top of the run matches the colour scheme of the station at the bottom, and over the road from that, Saltburn Pier, which celebrates its 150th birthday next weekend. An operator in a smart uniform issues the tickets for our £1.10 fare, and we enter a wonderful cabin with stained glass windows which transports us on our short descent to sea level. It only takes a minute at most to complete the 207ft trip, but it sure puts the ‘fun’ in funicular, as I am obliged to say (see also: Bridgnorth).

‘Did you hear the whooshing when you set off?’ a man in full tramway regalia called Peter asks as we get out. We did, you couldn’t miss it. ‘That’s because it’s completely run by water. It’s the oldest water lift in the country, in fact. We’ve got a reservoir which pumps water into a big tank underneath the tram, and once you get that little bump at the start, we’ve found the sweet spot where both the cabins are balanced out. We then add a little more water into the one at the top so that it slides down gently, which then pushes the one down here back up there. It’s ingenious how they thought of it.’

The ‘they’ are the Victorians. Separated from its pier for its first fifteen years, Saltburn’s tramway was the elegant solution to link the town to the coast below. The pier is another doozy. Rickety floorboards bounce as we stroll out over the grubby waves towards its head, where a pair of fishermen root inside a squirming box of juicy bait. The carcass of the steel works makes for a spectacular backdrop, with belching vapours still emanating from factories on the other side of the Tees, although the multi-coloured beach huts which line up along the prom add a spark of joviality.

‘Afternoon, young ‘uns,’ grins an old fella in a red summer jacket and white fishing hat once we make our way back to terra firma. ‘What brings you two here, then?’

‘It’s our wedding anniversary,’ we reply in unison, even though it was yesterday.

‘Wedding anniversary?’ he says aghast. ‘You’re not bloody old enough. Well, she’s not.’

‘We’re both thirty-nine,’ Eleanor laughs back. ‘Fifteen years in now, so I can’t get a refund.’

‘Fifteen years? Good for you. Sixty-two years it us for us two now,’ his wife appears right on cue from inside the tramway building and nods her hellos. ‘And I wouldn’t change her for the bloody world. C’mon, love, we’d better get cracking. Congratulations again, you two.’

With that and a wave, they hobble off towards a cafe.

We’ve not finished with Saltburn yet and stumble across a backstreet pub, which as it’s mid-afternoon in a seaside town will always fall into one of two camps. We are either going to be the only people in there, or it’ll be where all of Saltburn’s characters hang out. Fortunately for us, the Alexandra Vaults – aka, the Back Alex – is the latter.

Its walls rejoice in newspaper clippings, nautical artefacts, and a variety of unrelated odds and sods from all over the planet. It’s busy, too, with a well-lubricated gent yodelling Elvis Presley songs by the bar, a boisterous game of pool in the back room, and a landlady who takes no nonsense. A fortnight after our visit, she finds a man staggering in the beer garden at 3am with a cardboard box on his head. ‘He didn’t even cut eye holes in it,’ she told the local paper. ‘I was howling.’

There are three pub dogs on the hunt for treats, too. One of them, a cockapoo called Lucy pals up with us the moment we take a seat and plonks herself on my knee.

‘She’s feeling a bit sad,’ her owner, who with his flowing silver hair is a sure-fire Pink Floyd fan, says. ‘I took her to the hairdressers this morning, and they gave her a number two instead of a number six, so she’s in a sulk with me.’

His other dog, a yapper named Mia, is in a much better mood. She would be, though, as she is busy lapping beer off the fingers of at least two different patrons. She’s not at all interested in our pints.

‘Oh no, she won’t touch that stuff,’ her owner says while gesticulating towards my fancy-pants Punk IPA. ‘She’s only bothered with Guinness and real ale. We want to get her a CAMRA membership.’

We re-join the X4 outside Saltburn train station, whose line used to continue into the rear of the former Zetland Hotel a couple of hundred yards away. One of the very first railway hotels, it even had its own private platform, the remnants of which are still visible if you know which side street to sneak down. We have neither the time, nor the sense of direction to find it.

The bus slaloms around a brace of hairpin bends on the way to the coastline, and grunts its way back uphill to Brotton, where a chainsaw carving of a family of badgers sits at the village’s main junction. A vista overlooking The Iron Valley reveals itself from the hilltop, and it’s no great leap of imagination to envisage what Peter at the tramway described as ‘Dante’s Inferno’, with dozens of factories smothering the landscape in plumes of fiery smoke in years gone by.

Industry just about clings on today, with the Skinningrove British Steel operation have a synergistic relationship with the Caterpillar heavy machinery plant next door. But, with its key supply chain from Scunthorpe in danger of being throttled, the future looks bleak.

The road does a great impersonation of an oscilloscope, swooping, rising and throwing in the odd switchback to keep the driver on his toes as we edge into Loftus. Owned by the Zetland family – they of the eponymous hotel in Saltburn –legend has it they refused to include a clock face on the southern side of the town hall’s tower, as the residents there didn’t contribute enough money for the build. The ungrateful peasants. The truth, as usual, is much more prosaic. There were only a handful of houses to the south elevation, most of which were so far downhill that they wouldn’t have been able to see the clock anyway, but it’s still skimpy.

We’re soon at the top of another precipice, with jagged headlands ahead and a fluttering wave of greenery to the right. Conspicuous amidst the assorted bucolia is the world’s only polyhalite mine. Polyhalite is the residue from evaporated oceans, in this case the Zechstein Sea which dried up 250 million years ago, and is even a component of Himalayan salt. The seam ICL are plundering at Boulby is over 1,000 metres beneath the surface of the North Sea and is used as a fertiliser.

That only scratches at what’s here, though, as it’s also the site of the UK’s deepest laboratory, where scientists can work in an environment removed from background radiation. In among its 600+ miles of tunnels and roadways, the hunt is on for elusive particles of Dark Matter. NASA makes use of it as a test bed for Martian vehicles, and for researching the extremophile organisms which live in the mine’s salty confines. I expect it’d come in handy should some blithering idiots press their big red buttons, too.

Settlements are few and far between, but the ones we do dash through are all beautiful. We don’t see the best of Staithes, its picturesque heart tucked away along a cobbled lane inaccessible to our chunky carriage, but tiny Ellerby takes things up another notch. It should be a founder member of the National Registry of Outrageously Cute Villages, with a forest of pink clematis smothering the walls of its pub and neighbouring cottages.

We gain altitude again, but you know it’s serious when road signs warn you about a hill which is still four miles away. It’s a one-in-four drop from the cliffs at Lythe Bank, which reach 200 metres above the sloshing sea, now the same shade of silvery-blue as the clouds overhead.

‘Turn back now, it’s not safe,’ the signs plead to those towing a caravan or hauling an HGV. The countdown ticks by each mile with pictograms showing an alarming ‘25%’ triangle, trusting that any high-sided or unstable vehicles will do the sensible thing and find an alternative route.

The bus approaches with caution and it’s obvious as soon as we begin our dive that this would be a terrible place for your brakes to go on strike. Ours howl their discontent the whole way down. There’s a measly run-off road that appears to plummet onto the rocks below should you run out of tarmac, but regardless, it’s an exhilarating ride. Our destination comes into view as we round a bend. The old Metropole Hotel and Whitby Abbey making for tremendous landmarks atop of their respective bluffs on either side of the River Esk.

‘I don’t think I’d even want to drive up that, never mind down it,’ Eleanor says, puffing out her cheeks as we arrive in Sandsend. ‘That was ridiculous.’

‘Never mind driving it,’ I reply as we pass a gigantic yellow model of a bicycle next to The Hart Inn. ‘The Tour de Yorkshire is going up it at the weekend.’

‘On bikes? That’s even more ridiculous.’

The final stretch has us snuggling up to the sea wall, while steep slopes stripped of their grass leave an unattractive brown mass of bare soil to the other side. We are soon hoicked skywards again, before another abrupt tumble into Whitby’s harbour area.

Despite the numbers of tourists who fawn over its cobbled streets, the locals’ embracing attitude toward goths, and striking views from its twin promontories, I’ve never got on with Whitby. Part of this is because I saw a rat scuttling from a bin when we were last here about fifteen years ago, but I’ve either matured into the place, or strolling around on a quiet Thursday out of season suits me more. I suspect it’s the latter.

0 Comments