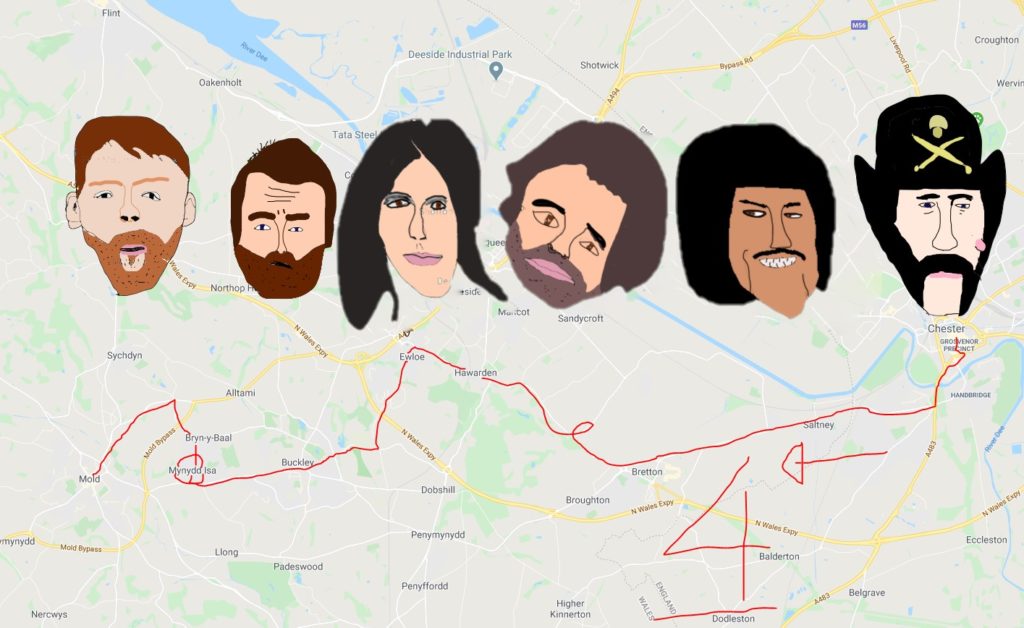

Route: 4, Chester to Mold

Operator: Arriva

Timetable: Every 30m (Mon-Sat; no Sunday service)

Time: ~1h 10m

Cost: £5.50 Arriva Day Ticket

Date of Trip: 13/7/19

Baby, It’s Mold Outside: Ian & Eleanor

‘Is that a return?’ asks the cashier at Wrexham General’s ticket desk.

‘No, just a couple of singles to Manchester, please,’ I reply.

‘Are you sure, love? It’s only 10p extra each.’

‘10p to come back to Wrexham? Sold.’

Fast forward a fortnight and we’re in Chester railway station, using up a good eight pence of those return tickets. Thomas Brassey, a local lad whose Cefn Mawr Viaduct left us agape on our original journey to Wrexham, has attracted an international fan club on the concourse. Three gleeful Thai women crack out their strongest Instagram poses for photos next to his brass plaque. I never knew he was this popular.

The bus to Mold leaves from outside the main entrance. Its driver sports a natty set of skull and crossbones braces, and we ask him for a day ticket.

‘Where are you going?’ he says, eyeing us up with suspicion.

‘Mold,’ Eleanor replies. ‘Then maybe onto Wrexham or Denbigh. We’re not too sure yet.’

‘It’s a different bus for Wrexham. You’re after the one behind me.’

‘I know,’ she says, nodding at me. ‘But he’s always wanted to go to Mold.’

‘Well, I promise he’ll never want to go again.’

We take our tickets and seats.

‘That’s a ringing endorsement, isn’t it?’

‘I don’t care,’ I say, a grin spreading to my cheeks. ‘We’re off to Mold. I can’t wait.’

First, though, we’ve got to pick our way through Chester’s pedestrianised centre. It’s a delicate crawl along Frodsham Street, slaloming between metal-wrapped wooden posts and flesh-wrapped shoppers. It’s an imposition too far for one couple.

The man has bullish arms camouflaged beneath a jumble of tattoos that extend along the side of his neck. She wears false eyelashes long enough to terrify a tarantula, and a skinny t-shirt with the slogan ‘Too Glam to Give a Damn’. Her seething response when the driver dares beep for them to shift out of the way suggests that, if anything, she somehow needs to become even more glam.

A stag group, 30-strong, makes its way to the races past St John the Baptist Church, where a cluster of medieval time travellers in brown tabards have set up camp on its lawn. They’re cooking what I assume to be an authentic dish in a cauldron – jugged ferret, cat broth or fox tail stew, perhaps – with one long-haired re-enactor throwing me a smile as he stirs. I reciprocate, but being used to derision from the public, he freezes for an awkward moment before glaring back at his steaming pot.

The stags don’t have far to reach the nags. On the banks of the River Dee, Chester Racecourse is the oldest circuit in the world. Thoroughbreds have galloped around its one-mile-one-furlong loop since at least 1539. Instigated by Chester’s then-mayor, Henry Gee, the popularity of the meetings gave birth to ‘gee’ being used as a nickname for horses, which mutated over time into gee-gees. The races always prove that putting a suit or massive hat on someone doesn’t mean they can now handle their drink. By teatime, the city becomes choked with lairy lads and lasses, swaying and tottering up Watergate Street on their way to colossal hangovers and texted apologies.

Flanked by hotels, oversized B&Bs, and even a croquet club, the road out of Chester meanders into Saltney, straddling the Anglo-Welsh border at Boundary Lane. Once we cross it, the signs become bilingual, but with Chester’s prefix still on the phone numbers. Clouds gather as we approach the windowless Airbus factory in Broughton.

We don’t catch any airborne activity today, but we once saw an Airbus transporter plane land. They’re an incredible sight, and thanks to their resemblance to a beluga whale – a flying beluga whale, no less – they are by far the cutest aircraft since Jimbo and the Jet Set. A trio of plane spotters are here for the long haul, though, and press up against the fence at the bottom of the runway, expensive camera lenses at the ready.

The bus continues towards the Deeside Enterprise Zone, a name which in another universe evokes thoughts of tech start-ups, product innovation, and pioneering research. This one, however, is a glum industrial estate where we change drivers. The replacement for the man with the skull and crossbones braces is a Teddy Boy with a towering bouffant. It’s feathery in construction, but held firm by an ozone-scorching jet of hairspray.

Wild grasses and cow parsley stud the verges as the bus climbs to Hawarden. The North Wales conurbation gets a rough press, and while it’s true that Flint, Shotton and Connah’s Quay aren’t easy to fall in love with, Hawarden (the ‘wa’ is silent) is a regional exemplar. Sturdy cottages and converted stables point the way along its handsome high street.

William Gladstone lived at the village’s castle, and in December 1868 was chopping down a tree in its grounds when he learned he was to become Prime Minister for the first of four spells. The castle is now in the hands of his great-great-grandson, Charlie, who rather than going into politics, became an A&R man, signing The Charlatans and managing They Might Be Giants.

Next up is Ewloe, whose biggest claim to fame is that it’s where Michael Owen bought all the houses in a cul-de-sac for his relatives. Not far behind is when the former footballer described the village as being “near Cheshire” when the Owens appeared on Family Fortunes. A holly bush, which will have looked harmless when planted, has consumed Wood Lane’s pavement, and is primed for school bullies to shove their nerdy prey into its spiky prongs.

The properties shrink from chateaux to bungalows the further uphill we head, topping out at Burntwood, where a keen Edward Scissorhands has snipped an abstract woman into three spheres of topiary. Drury Lane (not that one) leads us to Buckley, an unremarkable place with a remarkable music venue.

Despite Buckley having a population of just 15,000, The Tivoli was an essential stop for rock groups touring the UK from the 70s to the 90s. Radiohead, Oasis, PJ Harvey, Jeff Buckley, Motorhead, Thin Lizzy, and yes, Lawnmower Deth all came through in its heyday. It dispensed with most of the bands for the thick end of 20 years, but has rediscovered its roots of late. Although tribute acts and faded hair-metallers make up most of the performers nowadays, in a climate where there’s been an ongoing bonfire of live venues, The Tiv’s resurgence is cause for celebration.

The Black Lion and Black Horse pubs face each other across Mold Road, as we head toward Mynydd Isa. It translates as ‘lower mountain’, although there’s still a lengthy drop before we reach the River Alyn’s valley floor. We take an extended circuit of Mynydd Isa’s housing estate, emerging further up the hill than when we entered, picking up extra cargo in the shape of a dozen more passengers. Two of them are a dad and his excited son. The kid tells the whole bus that he turned four last week and he can spell his name now, ‘Wi. Ih. Luh, Luh. Will. That’s me!’

It’s only five minutes until we arrive in Mold. Mold. What a bizarre name for a town. Its native spelling, Yr Wyddgrug (‘err with-grig’, give or take, meaning ‘the tomb mound’), emolliates the tongue with its unfamiliar shapes, but emerged later than its English counterpart. Even so, wanting to know how to pronounce it prodded me in the mid-00s into learning Welsh. I’ve forgotten most of it now, but can still say please, thank you, and ask for a pint of beer or two lots of fish and chips. It’s a lexicon which has served me well in Snowdonia.

Mold has been on my radar for years. Decades, in fact. Its name always stood out on the drive up to my nana and grandad’s caravan in Towyn, and at long last here we are. It’s nowhere near as disappointing as the skull and crossbones guy said it’d be, either.

The bus station has a soaring sculpture by the stands. The county council commissioned ‘Machina’, a three metre tall carved stone block, in time for the station’s opening in 1996. Its hyper-modern styling is incongruous, especially with a bevvy of pensioners eating boiled ham sandwiches on the octagonal benches at its base. That said, it’s an improvement on the usual stern statues of dignitaries, even if I haven’t got a clue how it represents ‘art in engineering’ as its plinth suggests.

Right then, we’ve got some exploring to do.

0 Comments